Occasionally I see testimonials from people who use some trendy tool to manage their digital notes, like TiddlyWiki, Obsidian, Logseq, or Notion. And I’ve begun to feel not only disinterest, but a faint revulsion at the idea of using one of these apps. Other people are welcome to do so, and they may even get a lot out of it, but I’ll stick to my trusty folder of plaintext files synced between phone and computer, thank you. I’ve used those sorts of apps in the past, and I’m not going back.

But hold on, a text editor on top of some files counts as an app too. Especially since nowadays apps like Obsidian work straight off text files, no company will get ahold of your personal data either way. So what’s the difference really?

Mmmm, shiny rock.

The difference is that unlike these apps, text files are not manipulatory. This is not to say that every single notes app is a predatory piece of malware which will coerce you into doing microtransactions. Just that they remove friction around certain aspects of note-taking, and thus encourage you towards them. That’s the very point of these apps!

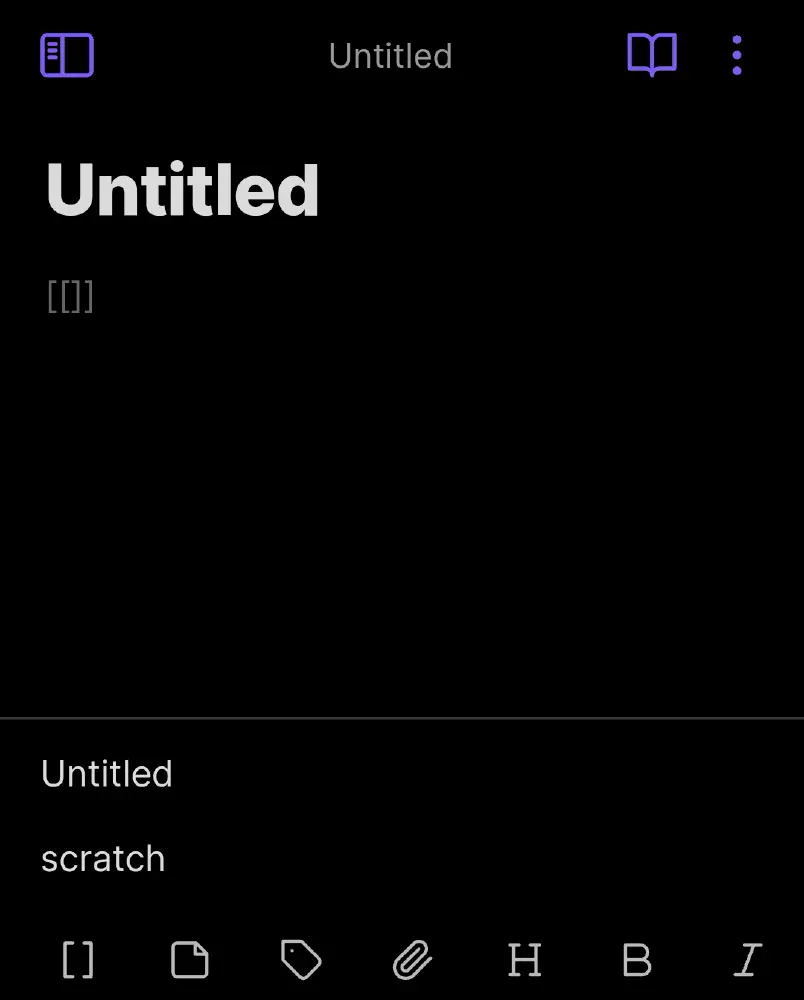

Hold on, I just installed Obsidian on my phone to find a relevant example. I picked a folder to work in and made my first two text files. Immediately, the name of the file is displayed as a heading.

That’s because in Obsidian, each file is intended to be a single unit of information on some topic, and to be linked together so you can view them in the knowledge graph (one of the app’s big selling points). And oh look, the first two buttons in the editor allow you to quickly link notes together. The two files I made are named Untitled and Scratch; at the bottom a menu pops up so I can select from either to link to. Creating a knowledge graph is now frictionless.

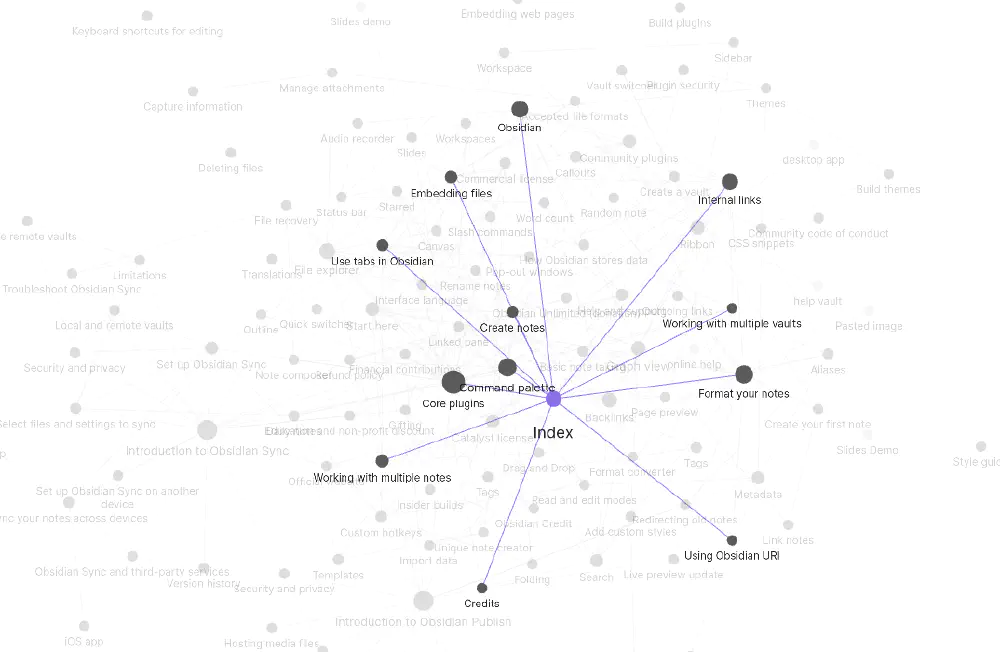

Part of the knowledge graph for Obsidian’s documentation, available to view on their website

Suddenly, I’m tempted to break my notes down into self-contained chunks and link them together at every opportunity, just because it’s so easy now. This pesky app is manipulating me by being nice to me!!

By contrast, plaintext files are designed without a particular use in mind. (In fact, I’m not sure to what extent they were designed rather than just being the bare minimum of a human-readable file format.) There’s nothing they particularly encourage you to do, except for write sequentially within each file, which seems unavoidable to me.

But what if I wanted to make a knowledge graph? Or perhaps I want to add a timeline or a kanban board (like Notion has) or skim-read a lot of files at once (I believe Logseq allows this). No, I still wouldn’t use any of these apps. Why? Because they are not as simple. And, as Analog Office writes, simple tools foster complex uses.

Text files are so basic that they are limitless. I use mine to store my bookmarks, shopping list, diary, schoolwork, offline versions of webpages for easy reference, and even part of this website. Derek Sivers has written about many other sensible benefits of plaintext. If I want to add structure and metadata, I can sort things into folders, or add my own frontmatter or tags; there are no limitations1. If I want to add basic formatting, I use the Markdown conventions.

Of course, text files can’t do literally everything. For example, I still use a calendar app because I like to quickly visualise my schedule. But that’s all. For any other notes, I won’t limit myself with specialised tools.

-

Often I find that doing this extra organisational work was unnecessary. After all, it’s very easy to search within and across plaintext files. ↩︎